Phil Stubbs delves into the initial development, writing and financing of The Man Who Killed Don Quixote.

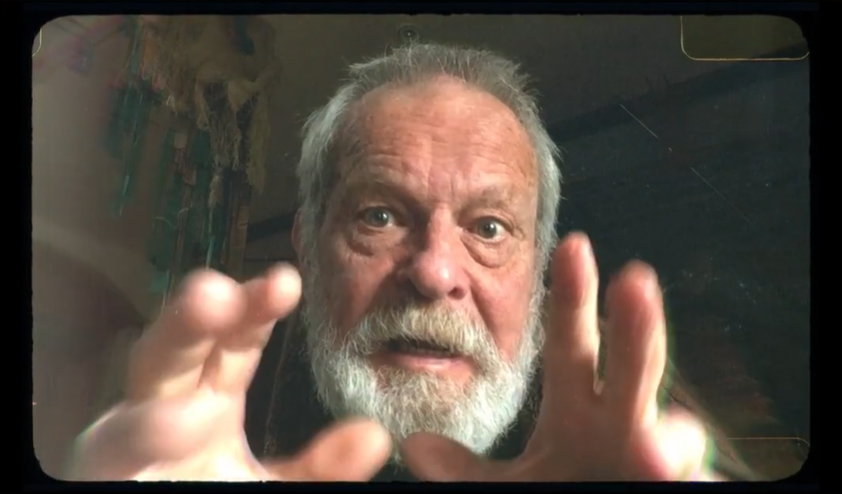

Terry Gilliam snapped just before presenting the UK premiere of Fear & Loathing (pic by PS)

Scotch in hand, Terry Gilliam sat down in the Edinburgh ABC cinema bar1. He wore a hat, leather jacket, long hair and an exhausted demeanour. His new picture, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, had had its UK premiere on the previous day, as part of the city’s film festival. This was August 1998. He had completed the film’s postproduction a few months earlier in May, just in time for that year’s Cannes Film Festival, and in the same month it had been released in the USA. In order to finish it in time, Gilliam and the postproduction team had worked long, hard days, which had left the director extremely tired. As a result, throughout the summer he had done zilch development work for his next film project.

I asked him if he had been offered scripts. He said, “Tons of them. But I haven’t read any. I still haven’t got this one out of my system. I went away to Italy for three weeks, brought all this work along, scripts to read. Didn’t do any of it. And I still haven’t got around to it. I’m just knackered. It reaches a point where I hate the film because it won’t let me go.”

He continued, “I really need to start thinking about another project, but on the other hand I don’t seem to be motivated to do anything.” He told me he had had enough of making films in America for a while. “There’s a side of me that wants to do something in Europe now. I want to put Hollywood away for a bit.”

I suggested that this presumably meant that Don Quixote might be more likely. He replied, “I’m not happy with our script. But I have some bold ideas on how to change it: a film called The Man Who Killed Don Quixote.” He said that this would allow him to use what he wanted from the book, rather than concentrate on the whole thing. And that is all he would say about it.2

***

When Gilliam finally settled down to work, later in the year, it indeed was the Quixote project to which he returned, and his approach was radical. The director recalls, “I realised that I couldn’t do Quixote as Cervantes had written him. I thought: can I make a movie that tells a tale that captures the essence of Quixote without relying completely on the book?”3

Gilliam’s solution was to simultaneously return to another project, an adaptation of Mark Twain’s “A Connecticut Yankee at King Arthur’s Court”, in which an American with knowledge of 1880s technology receives a nasty bang on the head, and is mysteriously transported back in time to Camelot. The director’s “bold ideas” involved mashing up the two texts.

It was the anachronism already present within Cervantes’s novel that led Gilliam to his idea. He explains, “The key to Quixote is that he is a man from the beginning of the 17th century, seeing the world as if it were the 12th century. But how do you show the 17th century character reimagining the world as if it’s the 12th century? Because for a modern audience, it’s just the same thing.”4

“One of the things I thought was important was that we had to establish a modern equivalent. So we took a modern man – an advertising executive – and we threw him back into the 17th century, which is as good as the 12th century for the modern audience. So that was the script we had: a modern man somehow thrown back into the 17th century, where Quixote thinks he is Sancho Panza, his realist sidekick.”5 This was a natural direction for the filmmaker, since comedy deriving from anachronism has been a key aspect of the Monty Python films, and some of Gilliam’s own pictures.

Such blending of appropriated texts should not have been a shock. This sort of thing had been detectable in Gilliam’s signature work for a number of years. For example, Brazil mixed together elements of George Orwell’s 1984 and Franz Kafka’s The Trial. And Munchausen took the episodic original tales of Raspe and structured them with a narrative reminiscent of The Wizard of Oz.

The contrast between Don Quixote and the man he believes to be Sancho would enable the differences between the two to be a major theme within the work. Gilliam said, “The advertising executive is an asshole who sells dreams, who uses dreams to sell. It just seemed right, for him to get caught up with the ultimate dreamer, the great fool. He becomes a servant to a 17th century lunatic.”6

Gilliam’s approach brought other benefits. First, the character of Quixote is no longer the protagonist: it is the modern man who is responsible for giving the story forward motion. Thus the narrative problems resulting from having a mad leading man evaporated. The change also enabled Gilliam to place autobiographical elements into the script, which enlarged his signature on the piece.

Further, it allowed the director to place a young, charismatic actor as the star of the vehicle, and also allow much of the dialogue to be in the modern vernacular. Intentionally or otherwise, both of these would be likely to improve the box office potential of the picture, which would be crucial to gaining interest from investors.

***

With these ideas inside his brain, Gilliam turned to Fear and Loathing co-writer Tony Grisoni on the script for The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. Grisoni recalled reading the adaptation by Gilliam and McKeown, “It was called something like The Adventures of Don Quixote. I thought it was a great script, full of wonderful things, but I wasn’t sure of the point of trying to squash these two volumes into a feature film.7

“Terry launched into this whole thing, the idea of a young, modern, arrogant man. A man who tries to control everything, who gets flung back into Don Quixote’s world, and gets cast as Sancho Panza, Don Quixote’s squire, a servant to a madman, in a world over which he has no control. This sounds like a good start to a good tale.”8 As a result of the scriptwriting sessions, the modern advertising executive was given a name: Toby Grosini.

Grisoni recalls the initial scriptwriting as being fun, hard work with no clear split of responsibility, “I’ve never worked with Terry where anything was distinct at all. Part of the joy is that it is play. What you have to do is to jump in and play. And it is quite hard play because you do it for a long time. I remember that we’d act out scenes in a very natural way. We didn’t stand on a stage performing, but we’d just go through scenes and play different roles. Then we’d swap the roles that we played. By doing this, we understood the sense of the scene, the timing and how the jokes work. I would then go away with the material. I’d write and then send to him and then we’d meet up again and go over the script.”9

Grisoni continued, “Meanwhile Terry would say, ‘I had a go. I had a look at that scene and I’ve got a new version here,’ and Terry would often say things like, ‘I managed to destroy the work that you did!’ Even though it’s a joke, I thought: well you’d better send it to me then. Then I would have a look at it, and of course he hasn’t destroyed it totally, but of course the destruction always brings a new idea or a new twist or an interesting take on something, or a new element. Then you incorporate that. We’d talk, we’d read the script, we’d have those ideas. I made sure I’d got many notes, so I could go away and piece it together and do the writing and then come back and do some more. It was quite a loose arrangement.”10

Reflecting further, Grisoni shared more details of their working arrangements, “I know that everyone likes the image of Terry being a crazed, out-of-control madman. But he’s not. He’s actually very disciplined. You can’t make a film unless you are disciplined. His take on a script is very, very good. He’s got a very good eye for a script. He understands structure of a script. This might sound to be rather dull, but he’s got a very good eye for structure. Of course Terry is a very visual filmmaker. But he’s also a chatterbox. He does a very funny thing with some dialogue: sometimes he’ll start talking non-stop. It’s very funny, very stream of consciousness. This method makes him free to come up with ideas, to write something which is freed of the rigours of the framework of the screenplay, which we can then go over and explore.”11

While Gilliam and Grisoni were writing, the director still managed to escape to various parts of the world, in part to publicise Fear and Loathing. Gilliam went to the San Sebastian film festival in September. He then went to a collect an award in Athens alongside Terry Jones, Emir Kusturica and Michelangelo Antonioni in October. In November, he went to a retrospective of his films in Minneapolis, and a Q&A session in New York City. Then in December, he visited the Havana Film Festival to present Fear and Loathing.

Gilliam was pleased with the resulting script, adding that “In the end I feel that Cervantes would quite like what we had done. I was able to use the best of Quixote, the bits I really liked, and weave another tale around it.”12 Of course, splicing the two texts together would be perceived as heresy by many. Upon hearing of Gilliam’s plan at the time, Richard Lester joked, “I think they’ll kill him in Spain. They take Quixote quite seriously!”13

***

A draft of the Quixote screenplay was completed early in 1999, ready for Gilliam to start securing the right cast. Gilliam called Johnny Depp, for whom the part had been written, and sent him the script. Depp was keen to work with the director again, saying, “Having experienced Terry on Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, I really loved the process. There was a great energy. I think we worked very well together. We had a great time. The initial thing for me on Quixote was the opportunity to work with Terry again.”14

Conveniently, Depp loved the script. “I was blown away by the screenplay”, he said. “I felt that I was reading this great book. It didn’t read like a screenplay, it felt like this beautiful, epic, hilarious poem. My character is the complete opposite to Quixote, the great dreamer… chivalrous, beautiful, romantic… And there’s Toby, this modern machine – this horrible, vicious, modern man.”15

Then the search was on for Don Quixote. Luckily, Gilliam’s regular casting agent Irene Lamb had been thinking about this since the director’s first attempt, “We’d started this so many years ago, and we’d obviously thought about all sorts of people here [in the UK], but now it was a totally different script. I’d seen Jean Rochefort in a number of films, and it was not until I saw Wild Target in 1996, that I thought: that’s Quixote.”16

Lamb kept her discovery to herself until Gilliam was ready to proceed with Quixote. “When Terry called to say we’ve got to find Quixote. I said, ‘I’ve got him – Jean Rochefort’. [Terry] knew the name but couldn’t put a face to it. So I got Terry to see Wild Target, and he thought Jean was great.” Discussions with the French actor took place, and then, coincidentally, both Depp and Rochefort at the time were about to get awards in France. So Gilliam jetted to the country and introduced the two actors. All three got on well, and the two key acting roles were in place. If only the funding of the picture were to be as easy…

***

In 1999, Gilliam was determined to aim for solely European funding for The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. The director longed to make a big budget film with no American involvement.17 In this endeavour he was helped by his old pal Ray Cooper, who at the time was a producer at @radical.media18. Cooper explained, “In Europe, Terry was less likely to have artistic interference. He would be able to get on with making his film the way he wanted to make it. He was highly likely to end up with a film on the screen he wanted to see.”19

Gilliam himself gave two reasons for opting for European-only finance. The first, which backed up Cooper’s point, was that “I wanted to be free from Hollywood’s influence. What we desperately need is a power base to make movies in Europe that aren’t informed by an American viewpoint, which will always happen when ‘British’ movies are funded by Hollywood studios.”20

The second reason was “to contribute to the construction of a solid film-making base in Europe. Even during the last heyday of British film-making under David Puttnam, which included films such as The Mission and The Killing Fields, few of the profits returned home. While British individuals made money, the bulk of the profits went back to the Hollywood studios.”21

Initial discussions to fund the picture were held with Working Title, a London-based production company who had been responsible for Four Weddings and a Funeral, Elizabeth, and a clutch of Coen Brothers films from Barton Fink to The Big Lebowski. Their track record suggested they would be an ideal outfit to fund Gilliam’s Quixote. However, discussions did not lead to a deal, and Working Title pulled out.

Working Title was partnered and funded by PolyGram Filmed Entertainment (PFE), which in turn was controlled by PolyGram, an Anglo-Dutch entertainment business majority-owned by Philips. Yet by the end of 1998, Working Title was owned and funded by Universal following the sale of PolyGram to Seagram (which owned Universal). Therefore by this time, despite the arms-length autonomy that it enjoyed from its parent company, Working Title was no longer in any case able to provide Quixote with European funding.22

Gilliam then picked up with Sarah Radclyffe Productions to help guide the project to full funding. Radclyffe is a UK-based producer, who had departed from Working Title in the early 1990s. Radclyffe and Gilliam were initially successful in getting deals with both Pathé Productions UK and Canal+.

Yet the money on offer from these two companies was not enough to fully fund the picture. Andrea Calderwood, a Scottish film executive working at Pathé at the time explained how unusual it was for a British film above $30m to be funded solely in Europe. “In Britain it’s still the case that every time you finance a film, it’s a minor miracle. It feels like a huge risk, and people have to feel as secure as they possibly can about investing in such a film. People have said they want to do this film and they want to step up to the challenge, but when it comes to that process they want to share the risk with as many people as possible. I think there is a general cautiousness about getting involved with someone like Terry, despite the film industry wanting to do bigger films – yet if you look at Terry’s previous films, they are not that expensive.”23

For the remaining loot, Gilliam and Radclyffe sought a German film fund. Such funds were popular with investors in Germany since, at the time, tax rates for individuals within the country went up to a maximum of 51%. A film fund allowed individual investors to become partners in the production of a film, and – importantly – expenses in making such a film were allowed to be deductible in the year they were incurred. The funds were free to invest in films made outside of Germany, with Merrill Lynch estimating in 2002 that 10-15% of US production was being funded by German film funds.24

Gilliam summarises the situation as follows, “At that point, German tax breaks were allowed. The government was allowing Germans to invest in movies, particularly Hollywood movies, and writing off their tax problems. For a while, Hollywood just ripped Germany off. These films were getting made and the money never came back to Germany!”25

The fund that the Quixote production tapped was the Munich-based MBP, which had been founded in 1999 by veteran producer Rainer Mockert. Initial discussions with Mockert went well, giving Gilliam the confidence that Quixote would soon go into production. At this time the budget of the project was a little above $35m,26 and MBP had pledged to stump up about half of the production budget.

Throughout the summer, Gilliam went to Spain looking for locations. John Beard was designing sets.27 Gilliam made further casting negotiations. Actors with whom he had previously worked joined the project: Ian Holm (Time Bandits, Brazil), Jonathan Pryce (Brazil, Munchausen) and Madeleine Stowe (Twelve Monkeys). Penélope Cruz, with whom Gilliam had never before worked, also joined the cast.28 Principal photography was due to commence in autumn 1999.

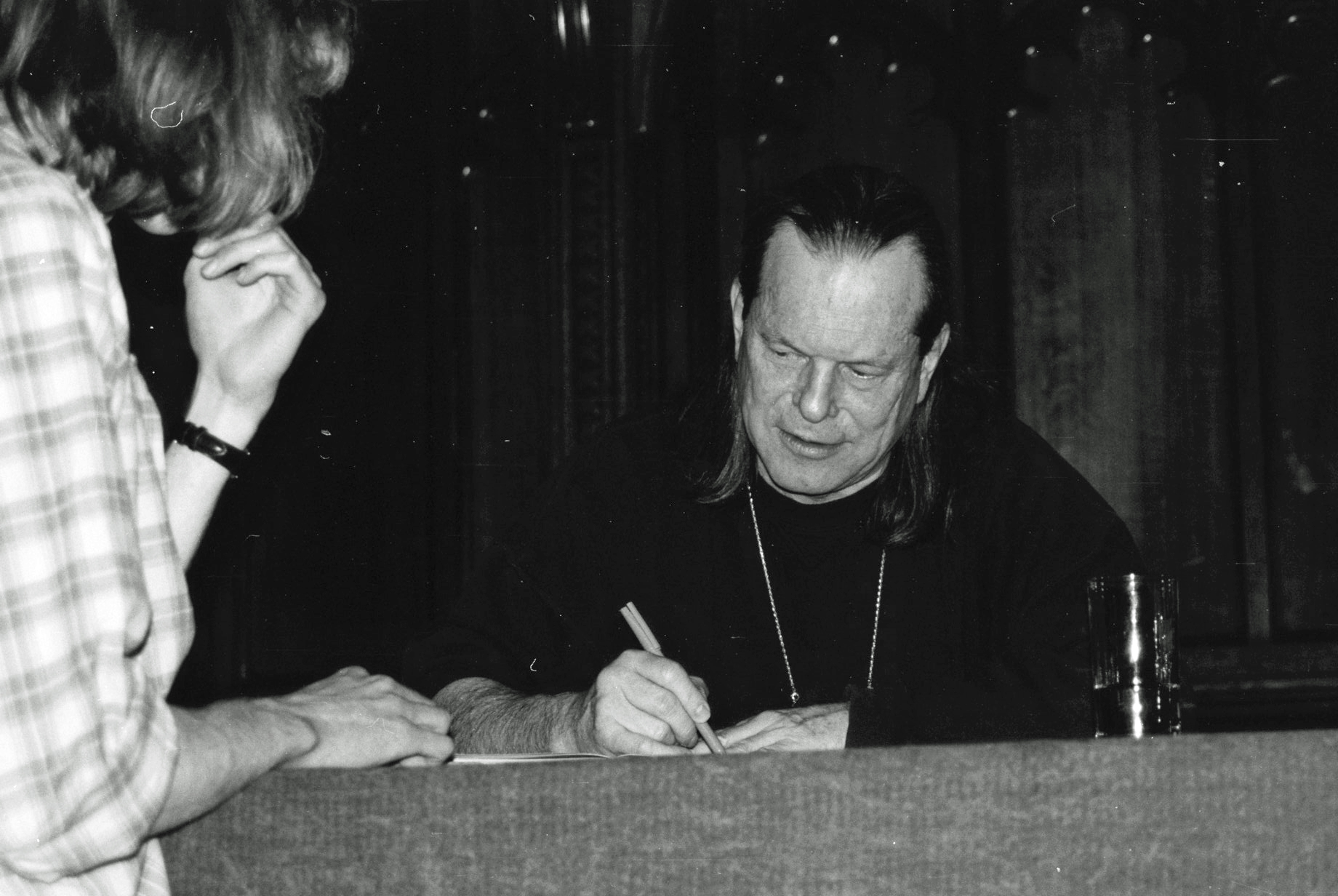

Gilliam signing books at Manchester University, March 1999 (pic by PS)

Such confidence in the project is reflected in Gilliam’s own communication from the time. In March 1999, he announced The Man Who Killed Don Quixote at a book event at Manchester University.29 Gilliam told the audience that he and Tony Grisoni had turned the novel into The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. Johnny Depp and Jean Rochefort were declared as cast members. In April 1999, Gilliam said in an email, “I just got back from a week’s recce in Spain for The Man Who Killed Don Quixote.”30 In June 1999, Gilliam wrote in a further email, that throughout the summer, he expected to be in and out of London “as we go into full prep for the film.”31

***

At the time, there were a number of Quixote projects in development, pre-production or production. Disney’s animation Don Quixote, long-planned, was having a burst of development, and in the late 1990s, the Brizzi brothers had created designs.32 A television film, Don Quixote, starring Jon Lithgow (Quixote), Bob Hoskins (Sancho) and Isabella Rossellini started shooting at the Costa del Sol, Spain in May 1999 for Hallmark. Based on a script by John Mortimer, it was directed by Peter Yates.

A BBC television film Donovan Quick starring Colin Firth as the title character was in development – with Donovan Quick and his sidekick Sandy Pannick up against the villainous Scottish bus company Windmill Transport. And 1998 saw the release of Torrente, a Spanish detective comedy directed by and starring Santiago Segura33, which derived a great deal from the sad knight. “Torrente is Don Quixote – without the nobility,” said John Landis to the New York Times.34

***

In July 1999, full preproduction – where sets are built, costumes are cut and stitched, scenes are choreographed and actors (ideally) come to rehearse – was about to commence. Yet the MBP cash was looking shaky, and Depp was considering a firm offer on another picture: The Man Who Cried, to be directed by Sally Potter.

“We were desperately trying to keep Johnny on board and he was committed to the film,” said Gilliam, “but Rainer just didn’t have the money. Legally the documents were there, but nothing was signed. He wanted us to put back the schedule – but a film is like air traffic control, you’re locking in all the pieces in order that everything moves forward according to plan.”35

Yet despite displaying enormous passion for the project, Mockert’s promised funding evaporated. And with no prospect of shooting, Depp opted for the Potter picture. Without full cash, and without the star, shooting could not start. At this point, Mockert leaves our story, except for me to note that his fund MBP went on to give significant cash to Last Orders, a project that Elisabeth Robinson and Fred Schepisi lined up after their own Quixote funding collapsed.

In desperation, temporarily putting aside his European funding purity, Gilliam sent the script around everyone he knew in Hollywood who might have the dollars to fund Quixote, but not without inflating the picture’s budget. Gilliam recalls, “There was one panicky weekend where we sent the script to most of the guys in Hollywood and said ‘We need $45m’. We thought that if we were going there, we want Hollywood money – everyone wants to be paid properly. So the budget went up to $45m to $50m. ‘And you have a weekend to read the script and say yes or no’. That’s really the way you charm Hollywood to get the money… but of course it was no, no, no!”36

***

In order to maintain what momentum there was, @radical.media provided temporary funding of $500,000. Then in August 1999 French producer Rene Cleitman, from Hachette Premiere, entered the story. He took over the production from Sarah Radclyffe, and vowed to achieve full funding by the end of the year.37 It was required by that time in order to ensure a spring 2000 shoot.

What Cleitman found so compelling about the project was Gilliam’s choice of actor for Quixote. The French producer said, “Even though I’m a big fan of Don Quixote, and of Terry Gilliam, what really fascinated me was Gilliam’s choice to cast Jean Rochefort. It’s what drew me to the project. The idea that an Anglo-American director thinks of Jean Rochefort for Don Quixote, stunned me and not just because I’m friends with Jean. It’s an artistic choice I find extraordinary.”38

Gilliam waited for news of a deal. During this time, he became involved with the Monty Python 30th anniversary television special for BBC2, broadcast on 9 October 1999. Some new sketches were filmed with almost all of the surviving Pythons (with Eddie Izzard replacing Eric Idle). Gilliam also made a single new animation.

The months rolled on. There was a mixture of gloom and optimism in an email from Gilliam in December 1999, “Windmills are taking up too much of my time with, as yet, nothing to show for the effort except frustration and depression. With any luck, I should have a definite response on Quixote next week. But then, I’ve been thinking this for months.”

Gilliam also confirmed in the same email that he had actually taken up a new project, an adaptation of Good Omens, a novel by Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman. Renaissance Films was developing a movie based on the book. No deal had been finalised, but Gilliam had been working with Tony Grisoni again, talking about a script. “At the moment, all they have to cough up is enough for Tony Grisoni and myself to get scribbling. If all works out we would probably be shooting Good Omens after I finish Quixote – whenever that will be.”

Yet in January 2000, the money to make Quixote was still not in place, and the project could not be green-lit for a spring shoot. Thus Depp, who had completed The Man Who Cried, disappeared to make Blow with Penélope Cruz for director Ted Demme.

As the new millennium started, Gilliam was hoping for movement, yet remained frustrated. He dispatched the following email in January: “My life is basically spent waiting for the money to be put together for Quixote. Deadlines float past like shit on the Thames. This week I head out for Paris for a final meeting (I hope), but it’s hard to maintain belief in this project the way it is dragging out. Clearly this is punishment for something I’ve done in the past – maybe it’s punishment for everything I’ve done in the past – if so, I’ll have a clear run the rest of the way.”39

In an email40 to the author at the start of February 2000, Gilliam stated that Quixote’s funding was uncertain, and was expecting a definite answer within one week. A further email41 four days later said, “Quixote is the in the final stages of either collapsing entirely or galloping off into immediate preproduction”. Yet neither of those outcomes happened. Instead, Gilliam had to play the waiting game again. At this time, Gilliam and Grisoni downed tools on their Good Omens script, because no deal had been finalised for that either.42

While waiting for the deal, Gilliam made an advert for a US company called Micron Electronics43. Entitled ‘Labyrinth’, Gilliam directed the 60-second television spot in London. Among the crew were cinematographer Roger Pratt, Ray Cooper providing music, and editor Hank Corwin. Gilliam also commissioned designs from the Brothers Quay for the advert.44

Stills from Gilliam’s Micron advert

Then there was cause for cheer. German investment fund KC Medien supplied the much-needed final chunk of loot. The Pathé and Canal+ money was still on offer. Says Gilliam, “The new investors were German dentists, and they were good for $16m. It’s funny that German dentists should be so rich, that they had to get rid of their tax problems by investing in Hollywood movies. So as a result of the German tax relief, we were able to raise $32m!”45

In April 2000, Gilliam confirmed his delight in an email, “It seems that at long last Don Quixote is up and riding. We start shooting in September. I almost believe this. Contracts haven’t quite been signed but I don’t see any looming problems. But of course, I’ve been wrong before. Anyway, I’m off to Spain to sort locations out.” And in early May, Depp confirmed he would play Toby. He turned down an $8 million offer from Jerry Bruckheimer to star in a Disney production called Take Down for Tony Scott. Depp’s then-partner Vanessa Paradis was also confirmed as a star.46

***

An aspect of the deal that would create a minor media debate in the UK was an award to Quixote from National Lottery funding. In May 1997, the UK government had named Pathé UK as the second franchise holder for lottery cash (of three). It was granted £33m to invest in British film, yet there were considerable strings attached, for example, each disbursement by Pathé UK had to be authorised by the then Arts Council.47 Andrea Calderwood secured £2m (then $3.2m) of public funds for Quixote, within the $32m overall budget. It was the largest amount of money ever awarded by the Arts Council to a single picture, and it was the last to be awarded by that body before the UK Film Council started to make the Lottery awards.48

Alexander Walker,49 a critic based at the Evening Standard, had been a long-standing opponent of using lottery money for financing films. He said, “Gilliam clearly hasn’t been able to raise the money from the Hollywood studios and this is an indication of the way Americans are coming to Europe to grab the money from European funding sources. It is the last gasp of the Arts Council Lottery panel before the Film Council takes over. The result is another Europudding50. The question must be asked: is this the best use of public funds?”51

Gilliam responded with an article of his own in the same newspaper, arguing, “Alexander Walker’s contention that I am an American film-maker exploiting the European funding systems is at best inaccurate, at worst absurd. Far from being an ‘expatriate American’, I am a British citizen and travel on a British passport. I have lived in the UK for 33 years – the majority of my life – and have made British television productions and British films. I am also a governor of that most British of film institutions, the BFI.52

“We are trying to alter the funding system in order to be able to make world-class movies in Europe and build up a long-term power base for future European film productions. If I am an example of an American director exploiting British public-funding bodies, then my advice to Hollywood film-makers is this: come to England, get yourself a British passport, begin your career in British television, get married, have kids, pay British taxes and settle down here. Then wait for 33 years before plundering the limited cash resources and public-funding bodies to make a feature film.”53

***

Terry Gilliam was to be found celebrating the Quixote deal at the Cannes Film Festival in May. An autumn 2000 shoot was confirmed. Speaking on a yacht with a TV interviewer, Gilliam said, “I’ve finally got the money for my next project! We’ve been here celebrating with all the people who finally coughed up enough money for me to start working again. They’ve been feeding me. So that’s why I’ve come – for a free lunch!”54

The Quixote preproduction started well. I met Gilliam in June 2000 in Notting Hill, London, in the temporary offices of @radical.media, since there had been an incident55 at their Soho office, requiring a short-term relocation. Having just returned from Madrid, the director looked cheerful. I wrote at the time that he looked rejuvenated, Munchausen-style. And he was thrilled to have finally secured firm full funding to make the picture, which he described as “Quixote Through the Looking Glass.”

Gilliam at the London preproduction office of Quixote, June 2000 (pic by PS)

All seemed to be going well until I received the following email on 27 August from the director, about a month before shooting was due to start: “Quixote marches nearer to the abyss each day…”

How did things go so terribly wrong? Find out in the third essential instalment, detailing the preproduction of the 2000 attempt to make The Man Who Killed Don Quixote.

To find out about Gilliam’s subsequent Quixote adventures, please come back to read further instalments.

Phil Stubbs has followed Terry Gilliam’s Quixote project closely since its beginnings in 1998. While visiting the Quixote set in 2017, he suffered an injury and broke three bones.

1. Now demolished and rebuilt, with only the facade remaining

2. All of these quotes, Author Interview, August 1998 at the ABC

3. AI, February 2016

4. AI, February 2016

5. AI, February 2016

6. Interview with Gilliam by Mark Kermode, in Lost in La Mancha DVD extras

7. Extras, Lost in La Mancha DVD

8. Extras, Lost in La Mancha DVD

9. AI, July 2017

10. AI, July 2017

11. AI, July 2017

12. Interview with Gilliam by Mark Kermode, in Lost in La Mancha DVD extras

13. AI, July 2002

14. Interview with Demetrios Matheou, in Lost in La Mancha DVD extras

15. Interview with Demetrios Matheou, in Lost in La Mancha DVD extras

16. Extras, Lost in La Mancha DVD

17. Gilliam speaking to Mark Kermode, in Lost in La Mancha DVD extras

18. Now branded as RadicalMedia, it is an global business whose output includes adverts, TV shows, music videos, documentaries, feature films and interactive media.

19. Extras, Lost in La Mancha DVD

20. Article by Terry Gilliam in Evening Standard, 28 April 2000

21. Article by Terry Gilliam in Evening Standard, 28 April 2000

22. From “Icons in the Fire” by Alexander Walker

23. Extras, Lost in La Mancha DVD

24. Background information within “Focus on German Private Media Funds”, Martin Blaney. From German Films Quarterly, Issue 3, 2004

25. AI, February 2016

26. Detail from “My latest is a disaster movie” by Sean O’Hagan, The Observer, Sunday February 4, 2001

27. From Ray Cooper interview in the Extras, Lost in La Mancha DVD

28. Ian Holm and Jonathan Pryce identified by Radio Times in October 1999. Madeleine Stowe and Penelope Cruz identified in The Guardian on 21 September 1999

29. The author attended this event, on 9 March 1999, held to publicise “Gilliam on Gilliam”, edited by Ian Christie and published by faber and faber

30. Email from Gilliam to Author, 25 April 1999

31. Email from Gilliam to Author, June 1999

32. Artist Register

33. More on him in the next instalment

34. New York Times

35. Quote from “My latest is a disaster movie” by Sean O’Hagan, The Observer, Sunday February 4, 2001

36. Extras, Lost in La Mancha DVD

37. This detail is taken from “My latest is a disaster movie” by Sean O’Hagan, The Observer, Sunday February 4, 2001

38. Extras, Lost in La Mancha DVD

39. Email from TG to Charles Alverson, January 2000

40. Email from TG to Author, 1 February 2000

41. Email from TG to Charles Alverson, 5 February 2000

42. Email from TG to Author, 1 February 2000

43. The advert can be seen here

44. AI with the Brothers Quay, 2001

45. AI, February 2016

46. Variety, Depp to don “Quixote”

47. From “Icons in the Fire” by Alexander Walker

48. “Row as Gilliam film gets £2m”, by Neil Norman, from Evening Standard, April 2000

49. Alexander Walker was a supporter of Gilliam’s Jabberwocky, but was scathing about Gilliam’s later films. Gilliam offers an explanation in his memoirs, Gilliamesque

50. Term popularised in the 1980s to describe stodgy European movies with funding & cast from several different countries.

51. “Row as Gilliam film gets £2m”, by Neil Norman, from Evening Standard, April 2000

52. Article by Terry Gilliam in Evening Standard, 28 April 2000

53. Article by Terry Gilliam in Evening Standard, 28 April 2000

54. This quote was from a TV interview (Sky News I recall) with TG during the Cannes Film Festival, quoted at Dreams: the Terry Gilliam Fanzine

55. I recall it was a flood, but it could have been a fire, or some other calamity