In January 2008, on the set of Terry Gilliam’s latest picture The Imaginarium of Dr Parnassus, Nicola Pecorini, its Director of Photography, keeps warm under a Peruvian poncho made from llama wool. On location in wintry London, it is tough to get through each of the 10-hour night shoots.

Despite the weather, Pecorini and the director collaborate efficiently, never far from each other. They share a working style that is extremely focussed, yet informal. Gilliam tells me that the working relationship between them has become instinctive. When it comes to choosing a lens for a shot, said the director, “Nicola and I don’t even talk about it anymore.”

In a previous interview with me in 2004, Pecorini told me, “The great thing about Terry is that he always allows the unexpected to intrude and mould what the movie is becoming. It’s great to have that freedom of mind that you often don’t find in the movies.”

|

Nicola Pecorini on the set of Brothers Grimm – pic by Francois Duhamel |

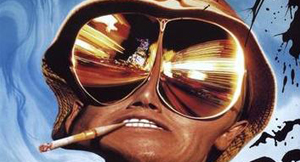

An Italian, Nicola Pecorini worked as an assistant photographer in the New York fashion world of the Seventies. Later in the 1980s he became an early pioneer of the Steadicam, and was involved with the design of new models. In fact, he set up the Steadicam Operators’ Association with its inventor Garrett Brown. Pecorini first worked with Gilliam on “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” (1998). They have subsequently worked together on a number of projects, most recently “Tideland” (2005).

I interviewed Nicola in early January 2008. This was towards the end of location shooting of “Dr Parnassus“, in London. Yet to come was the bluescreen work in Vancouver, now complete. And the conversation took place just two weeks before the untimely death of the film’s star Heath Ledger.

Away from the film set, Pecorini is affable, relaxed, and enjoys identifying and sharing the absurdities of life. Pecorini generously answered my questions at length, offering his distinctive insight into the project, and its place within the film business.

|

Nicola Pecorini working on Tideland with actress Jodelle Ferland – pic by Francois Duhamel |

Dreams: When did you start working on the picture?

Nicola Pecorini: Terry sent me the first draft of the script towards the end of 2006. I was in bed with a badly broken knee, resulting from a motorbike accident – so I was able to start thinking about it from the very beginning. Then started the usual excruciating process to try to put the project together, find a producer – and find the money. As with every movie, it’s a long and frustrating phase – and my previous experiences with other scripts of Terry – Good Omens, Quixote, Defective Detective, Tideland – taught me that a Gilliam project is particularly frustrating from this point of view…

Why is that?

Terry’s scripts seem to be always too difficult to grasp, and to be understood and embraced by the people with the money. I came to the conclusion that it’s merely a question of mental flexibility, of open mind, in a word: intelligence. The sad reality is that most executive, most self proclaimed “producers” are simply too stupid to understand the complexity and the high levels of poetry and artistry that are present in Terry’s scripts. All they can understand is the sound and smell – maybe the stench – of money. Anything that goes beyond that, anything that is not within certain well established parameters is seen with suspicion.

Art does not have much space within today’s movie business. Sometimes I have the impression that the movie industry suffers the same disease that TV is dying of: a constant trend in lowering the standards, the consistent effort of not to disturb. And “industry” is a terrible word for something that should be well above the economical parameters. Thought provoking work has no appeal, it’s dangerous and seen with suspicion. In other words, today’s movie makers are denying the very essence of cinema as a form of art. If the definition of art is “a product of human activity, made with the intention of stimulating the human senses as well as the human mind; by transmitting emotions and/or ideas”, then it’s quite clear that it does not fit with today’s mainstream interpretation of cinema. Unfortunately, Hollywood – and therefore the majority of other realities that happen to make movies and that follow the Hollywood school of thought and approach to movie making – seems to have fear of art, and that is a philosophical approach very similar to that of the Taliban.

What for you is the appeal of the script?

Well, it’s the level of poetry that is present in the script that appealed to me the most. Having shared Terry’s last 10 years of passions and frustrations, I totally understand where Dr Parnassus comes from. A tired man that has been trying to enlighten his fellow humans, to teach them to let their imagination fly and flourish, to consider the power of dreams as a richness and not as a burden. Parnassus IS Terry.

The script is the fortunate child of years of battle against the system, of frustrations accumulated trying to give shape to sublime ideas. Specifically the events of the last 7 years have generated the current script. Events such as the collapse of Quixote, the awful experience with the studio system with the Brothers Grimm and the criminal handling of distribution of that little pearl that, in my opinion, is Tideland.

I see the Imaginarium as the silver lining of these pains. I read the story as a fantastic sum of all of Terry’s artistic career: you can find in it all the elements that were present, in one way or another, in a veiled or blatant manner, in all his previous works. It’s definitely a very mature script and I firmly believe that all those out there (and luckily there are a lot of them) that love and appreciate Terry’s previous works will find that Parnassus is the apotheosis of Gilliam’s art.

What did you do during pre-production?

There have been two phases of pre-production. The first one I would define it as the goodwill phase: it went on from early 2007 to September. It was mainly aimed at focusing on how we could pull off such an ambitious and technically complicated project within a budget that by today’s standards was totally inadequate. In “normal” circumstances the total budget we have would barely cover the cost of visual effects alone. Terry produced a very comprehensive series of storyboards order to be able to break down shot by shot what needed to be done – and he hasn’t done that for a long time.

And normally this is a process that is done once there are money to be spent, people to be hired. I flew to London few times – at my own expense, of course – to sit in endless meetings where we tried to pinpoint the essentials, to simplify approaches, to find solutions. One of these meetings was attended by Heath Ledger who was in London filming The Dark Knight. He was so fascinated by Terry’s vision and exposition of the story that he decided he wanted to be part of it, at all cost, even as craft service! From that day everything started taking shape: we had the STAR! Therefore, all of a sudden, the money people were interested and a budget was found, even if it was inadequate.

In August we had our very first location scouts. At the time I was shooting a movie in Rome and I took advantage of the Italian habit of stopping for the “Ferragosto” week to come to London and scout, scout, scout. That was the week when we started having a clear idea of which way to proceed, which locations to choose, how much time we would have needed to complete each scene. But the project was still a wishful thinking: there were still no money in the bank, no salaries to be paid. The necessary people could not be hired. Generally people have the tendency of wanting money in order to work! It seems that only me and Terry were ready to work with no compensation. It actually fits very well with the Parnassus theme of the power of dreams versus the power of money…

It was only in mid-September that we could afford to start putting together a team. Unfortunately, because of the financial architecture of the movie we had to respect certain parameters of nationalities and therefore we could not necessarily hire who we wanted or who was available. Since then it has been a race against time. We had to start shooting within December because otherwise we would have lost Heath, who was committed to another project starting in March. We managed but we are still paying toll on the rushed pre-production and the lack of human resources – not that we do not have good people and professionals, it’s just that we do not have enough of them.

How much is actually planned in advance, and how much is decided on the day?

As I was mentioning on the previous answer we tried to plan every single detail in advance. Especially the Imaginarium sequences are broken down shot-by-shot, frame-by-frame. But even the most carefully planning cannot avoid the unexpected nor human failures in delivering what’s needed in a timely and precise manner.

We are currently carrying a half day delay on the schedule due to various technical mishaps. But it’s pretty good considering the complexity of the shoot. The wagon proved to be a much more complicated and cumbersome piece of equipment than expected. We have been very lucky weather-wise. Yes, we had to deal with extreme cold in the weeks before Xmas, but the much dreaded London pouring rain did not occur.

How different is getting through a shot with Terry compared with other directors?

With every movie, it’s a different story. With Terry we share a common vision of the “cinematic stage”, namely a 360 degrees approach to framing. We kind of reached a total symbiosis, without talking we always reach the same conclusions and adopt the same solutions. I find it very easy to work with Terry even if technically very difficult. Lighting for a 360 field of view is certainly more complicated than sticking to long lenses.

The major difficulty is to have other people understanding our approach. They have problems with us not wanting big video villages and blind areas. Again, it gets down to mental flexibility and capacity of adaptation. Unfortunately British crews seem to have developed a very “corporate” way of working, the department are very self absorbed and very often I get frustrated by this absolute rigid approach. Not to mention the total absurdity of the Health and Safety rules that try to make filming very slow if not impossible. If one should stick to the rules, one wouldn’t even start shooting.

What has been your happiest moment on set so far, and what do you like about how the film is developing so far?

I always try to have fun while filming. If not this job becomes far too exhausting and gruesome. Therefore every day I find moments of happiness. But on a more specific note the best moment has been realizing that all our cast is passionate and work well together. Heath particularly is a force of nature and certain days carries an enormous load on his shoulders. His skills are matched by his generosity and the result is a constant raising of the level of acting and performance, the great thing is that his fellow actors are definitely up to the challenge.

Nicola Pecorini’s website is at www.nicolapecorini.com